Use of Force models: Comprehension or confusion?

In a previous article, "Continuous Improvement": Real Gains, or mere lip service, I concentrated on the National guidelines for incident management, conflict resolution, and use of force: 2004, and the problems associated with those guidelines. In this article, I will focus on one particular aspect of those guidelines that should be of great concern to Australian Police.

"Which is a greater use of force? Punching someone, or pepper-spray?" If I had a dollar for every time I heard that question, I'd probably be riding a gold-plated Harley Davidson to my 100-foot yacht by now. The reason that question was asked so frequently was because neither legislation nor policy sufficiently explained the relationship between certain Use of Force options. Have you been trained enough to answer that question to a jury of your "peers"? How about to an internal investigator, or one from CMC / OPI etc?

In 1994, the Victoria Police conducted PROJECT BEACON, which was a training program in response to public (and media) outcry about the number of people shot by Victoria Police. (I am in no way criticising Victoria Police Officers for their Use of Force at that time.)

Part of this project was the establishment of a Tactical Options model that was to be taught to all Victorian Police Officers. This Model was then taught by other jurisdictions, and eventually made its way into the National guidelines in 1998, and again in 2004.

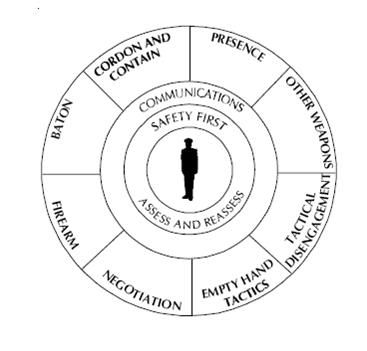

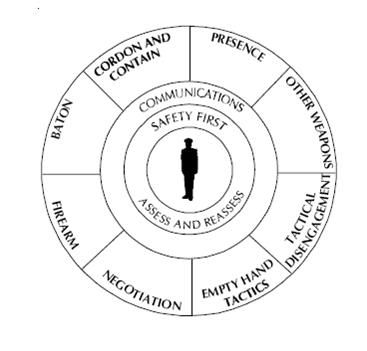

Figure 1

Let me point out some basic ideas behind this Situational Tactical Options Model, (see figure 1), which I have directly quoted from the National guidelines for incident management, conflict resolution, and use of force: 2004:

"Such a model provides a mechanism to aid police officers in the management of incidents";

"the model assists police officers to select the most appropriate option to achieve a safe and effective response to a variety of scenarios";

"Incremental models illustrate a step-by-step, linear progression in the level of force that is appropriate according to the level of resistance/threat displayed by a suspect/detainee, from minimal force (e.g., officer presence, verbal communication) to lethal force (e.g., firearms). There are two fundamental problems with the structure of incremental models. First, they imply the need to move through the incremental progression one step at a time. As a result, such models are very restrictive in terms of the tactical options available for selection at any point in time. Second, they can be viewed as uni-directional. This limits the scope for de-escalation of the incident";

I will comment on each point separately. Firstly, point 1 states, "Such a model provides a mechanism to aid police officers in the management of incidents". This point I agree with, and is one that needs to be understood by all. This model assists officers in the management of an incident.

Too many agencies in Australia are teaching our Police this model as an example of how to decide upon which Use of Force option to use. This is a dangerous practice that needs to cease. This is not a Use of Force model but a Situational Tactical Options Model. It is something that should be used by the senior Police Officer at an incident to refer to when resolving an incident. It is not a learning tool for Use of Force training.

"Hick's Law", to greatly simplify, states that the more options to choose from, the longer it takes to choose an option. If a Police Officer is faced with a threat, especially a potentially lethal threat, then that Officer's training should be such that they know exactly what option to choose in that situation. They should not be thinking about some ambiguous model with a multitude of options displayed in random order, most of which are not relevant to that particular situation.

The Association of Independent Schools, Queensland, (AISQ), created a research brief titled Best Practices in Teaching and Learning: What does the research say? (2001).

This brief outlines that the human brain learns patterns:

The search for meaning occurs through patterning. The brain is both artist and scientist. It is designed to perceive and generate patterns, and it resists having meaningless patterns imposed upon it (Hart, 1983; Lakoff, 1987). Meaningless patterns are isolated pieces of information that are unrelated to what makes sense to a student.

Implications for education: Learners are patterning or perceiving and creating meanings all of the time in one way or another. We cannot stop them, but can influence the direction that their learning takes. Although we select much of what students are to learn, the ideal process is to present the information in a way that allows the brain to extract patterns, rather than try to impose patterns.

So is a random assortment of use of force options better to teach Police with or an incremental model in a clear pattern that also articulates what force options should apply to particular threats? It seems obvious that a clearly-defined model is better to learn and understand than something designed to be ambiguous.

Point 2 - "the model assists police officers to select the most appropriate option to achieve a safe and effective response to a variety of scenarios." Ok, can anyone explain to me exactly how this model is supposed to do this? Police Officers do not carry around a copy of this model in their pockets to refer to when they attend at an incident. Too many, actually all, Australian police agencies think that displaying a model during a lecture will train Police to be able to cope with a critical incident in the future. To be blunt, this is a load of bull droppings.

The ONLY training method that will assist Police in the management of incidents is to firstly teach them the laws, policies, and methods in the classroom, and then rigorously train them and test them in extensive practical exercises. Staring at a model on a Powerpoint presentation, considering that the human brain can not easily memorise multiple components of a non-linear / non-pattern model, is not an effective training tool for managing a complicated incident under stress.

And how can an Officer, much less a member of the public or media, look at this ambiguous model and understand what the appropriate response is to an offender's actions? How would anyone be able to use this model to justify any level of Force used by Police?

Point 3 – "Incremental models illustrate a step-by-step, linear progression in the level of force that is appropriate according to the level of resistance/threat displayed by a suspect/detainee, from minimal force (e.g., officer presence, verbal communication) to lethal force (e.g., firearms). There are two fundamental problems with the structure of incremental models. First, they imply the need to move through the incremental progression one step at a time. As a result, such models are very restrictive in terms of the tactical options available for

selection at any point in time. Second, they can be viewed as uni-directional. This limits the scope for de-escalation of the incident"

I have major issues with this point, especially as it assumes that the model in Figure 1 assists Police in choosing a Use of Force option. Stating that a linear model implies anything is an illogical explanation chosen only to justify the authors' bias. There is no evidence to suggest teaching Police progressively different levels of Force means that they will start at the bottom and work their way up, or down. It is a clear guideline of where each Use of Force sits, and not a "map" to follow step-by-step.

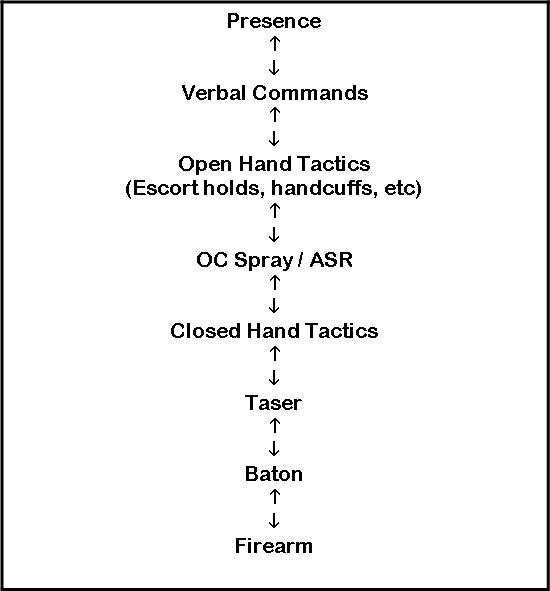

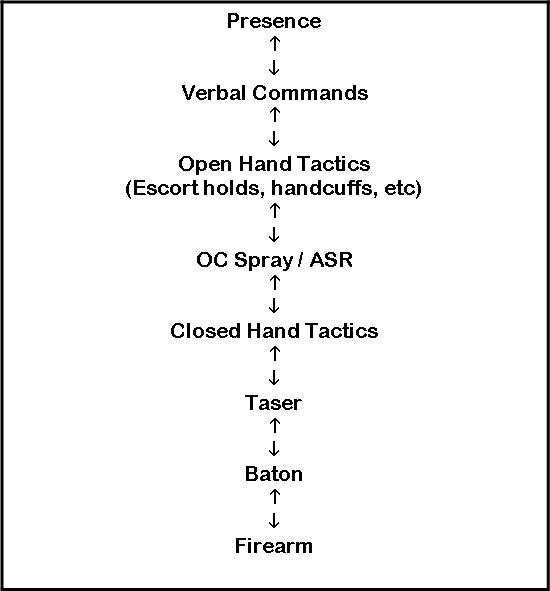

Additionally, a linear Use of Force model (see figure 2) is easier to explain to a Jury (and to the media), and assists in the learning process of Police officers, and their justification of Use of Force. A linear model shows the relationship between each Force option, and clearly illustrates to both Police and outside parties where each stands. There is no confusion as to which is greater.

Figure 2

The above points alone should be sufficient to not use the non-linear model in Use of Force training. The linear, or incremental, model allows crystal clear explanations and understanding of Use of Force by Police. Also, how many times have you read some "expert" in the media claiming that the Use of Force used by Police was excessive, and they should have used another option? Imagine if your Organisation (or your Union) could point to a linear Use of Force model to show that what the "expert" suggests is plainly incorrect?

Lastly, point 3 also states that a linear model "limits the scope" for de-escalation of Force. Say again? I am tired of academics and Police Managers assuming that frontline Police do not have the mental capacity to understand something, in an effort to justify not teaching a tactic. Ask yourself, how difficult is it to understand that if you use a particular level of force against a particular threat, and that threat is reduced, you reduce your level of force in response? Considering that Australian Police organisations are attempting to have Policing recognised as a "Profession", then our Managers and Academics should realise that today's Police Officer is a "professional". In other words, our Police Officers aren't as dumb as these guidelines insinuate.

To put it in "layman's" terms, do you really think that the Police Officers in our nation will not understand the concept of de-escalation of Force? And if you do not think they are intelligent enough to understand that concept, do you think the ambiguous models currently used will assist them?

The work done by Australian Police agencies to ensure that our Police use the minimum amount of force needed to resolve an incident is commendable. Our society expects our Police to resolve an incident with the minimum amount of force necessary, and to not be like "Dirty Harry" in their approach to offenders. However, when it comes to Use of Force, it should be emphasised to the public that Police will use the minimum appropriate force, and not just "the minimum". If the minimum force appropriate to a situation is spending ten hours talking to someone, then so be it. But that does not mean the very next incident does not justify punching a suspect, or even shooting them to defend the life of an innocent. Sometimes lethal force is the minimum appropriate, and though there will always be critics of this, society at large will understand this concept. However, having guidelines and diagrams to show the public and media will greatly assist in the explanation and justification of the "appropriate" amount of force used by Police.

Naturally the argument will arise that current training models and methodologies are suitable. Well, are they?

In February this year, the Executive Leadership Group (ELG) of the NT Police Force sent out an organisation-wide notice, which stated, "A decision has been made to raise the level of force to which Tasers can be applied. The intent of the amendments by ELG is to place the Taser just under that of the firearm and to ensure that all other options are ruled out before the Taser is applied."

Can anyone relate that to the circular and ambiguous Use of Force model that 7 out of 8 Australian Police organisations (including NTPol) use? They are effectively saying that the circular model is not sufficient, and are clearly defining the use of an incremental Use of Force model by ordering their staff to "place the Taser just under that of the firearm".

The problem with NTPol's directive is that is very restrictive in the usage of a particular force option, which seems to be guided more by an intent to protect the organisation than it is to providing useful and effective guidance to the Officers facing threats on the streets.

On the 17th of March this year, the Queensland Coroner reviewed four Police shootings. Although he cleared Police of any wrong-doing in relation to the actual Use of Force, the Coroner stated:

"I recommend that the Queensland Police Service review the operational skills training provided to officers..."

"Despite the earliest of these shootings occurring four years ago, no review of the incidents has been undertaken by the QPS to consider the conduct of its officers or the suitability of its policies and procedures....no opportunity for organisational learning has been utilised."

It should be obvious that reviews of incidents, policies and methodologies should be continually assessed, especially when the phrase "Continuous Improvement" is bandied about so much, but unfortunately it does not happen as frequently or as in-depth as it should. Just because your Use of Force policies and training models have not yet been criticised as lacking by a Coroner, does that mean it is perfect? Of course not.

Fortunately, there are other options out there, some of which are confusing or dated, but actually provide valuable training and policy tools to our Police. The preferred endstate of a Use of Force model, accepted by a Police organisation is one which "assists police officers to select the most appropriate option to achieve a safe and effective response to a variety of scenarios." I also propose that an organisation's Use of Force model should illustrate to investigators, the court, or a jury, what the appropriate level of force is in any given situation. It should also highlight the dynamic and fluid nature of incidents. So, I will examine some options with the following three guidelines:

1. Assists Officers to select the appropriate option to achieve a safe and effective response to a variety of scenarios;

2. Illustrates clearly appropriate options to outside parties; and

3. Clearly show the requirement to constantly re-evaluate available options.

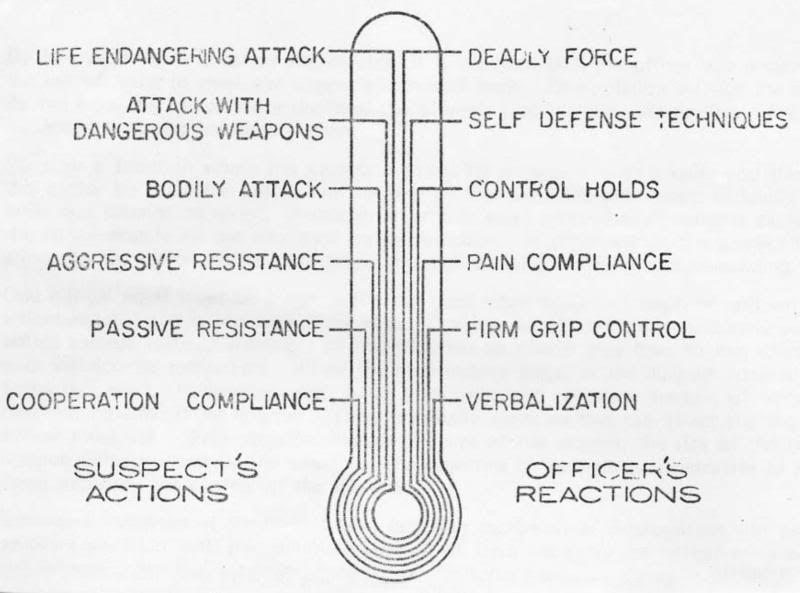

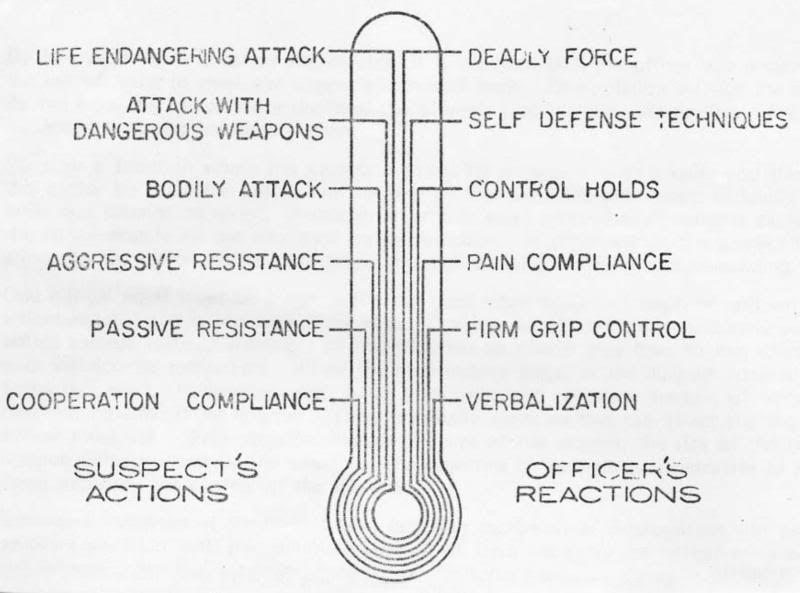

Use of Force models have been around for a while. Let's look at figure 3.

Figure 3

This model was used by the Los Angeles Police department in 1978, and was called a "Force Continuum Barometer". It clearly shows both a linear explanation of the Use of Force options available to Officers, as well as what is an appropriate Force option in relation to the actions of a suspect. This clearly shows a trainee or a jury what is appropriate or not. However, although it would have been a useful tool 30 years ago, it does not truly reflect the fluid nature of Policing. Neither does it reflect the tools at a contemporary Police Officer's disposal.

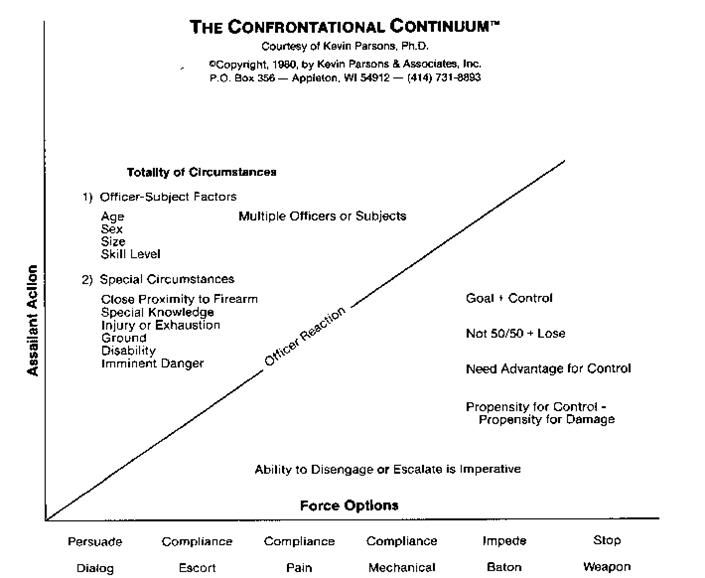

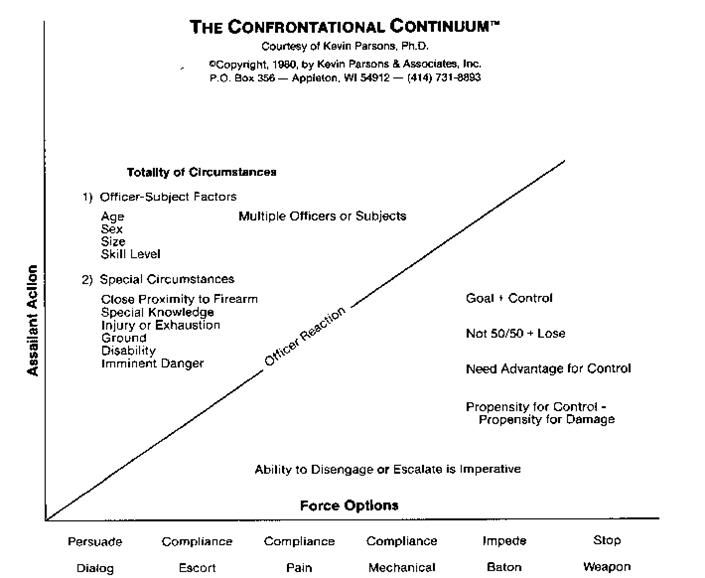

Figure 4

The "confrontational continuum", created by Dr Kevin Parsons in 1980, is an early attempt at trying to reflect the different aspects of suspects and their behaviour in a model that would assist Police in their responses. Again, this model clearly shows where each Use of Force option sits in a linear progression, which assists in training and justification of Force. Again, although it was probably a ground-breaking model in it's time, it fails to display the third point that I am assessing these options on. There is no indication of continuous evaluation.

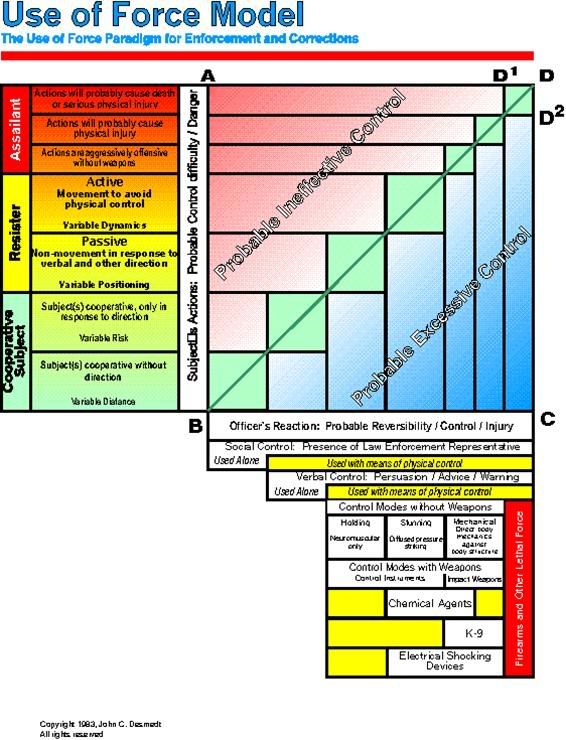

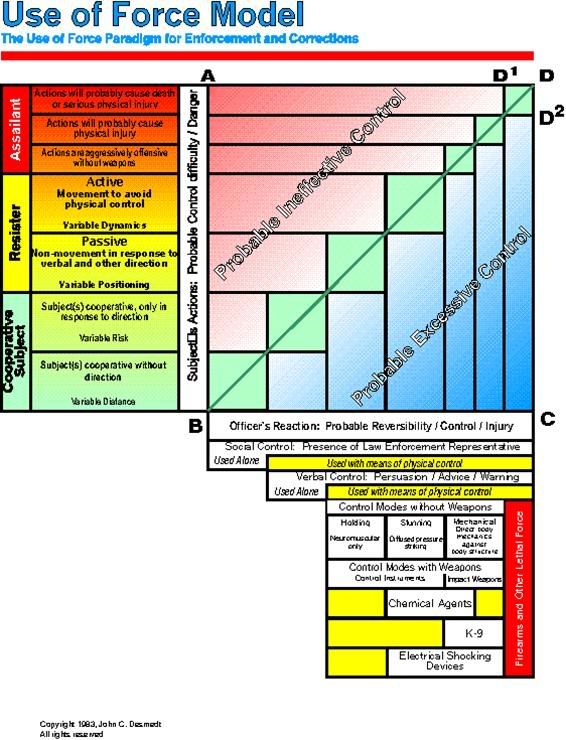

Figure 5

The above model, created in 1983 (and described as the "Original" Use of Force model), is again a linear progression chart, describing both the suspect's resistance levels, with corresponding appropriate Use of Force options. Although also showing the levels of Use of Force available to Police, it is a confusing model which also limits options of Police to the green area. This would be useful in limiting the number of options available to Police, (keeping in mind "Hicks Law"), but in this day and age of legal liabilities and the policy of minimum force, I can see this model as being a lawsuit waiting to happen.

As you can see, these models have not been getting simpler, nor do they show the Use of Force options in a random pattern, but clearly articulate where each Use of Force option sits in relation to other options. Remember, this is important in training Police in appropriate Force levels; assists Police in justifying their actions; and provides a clear representation of levels of force and appropriate options to those persons with outside interests.

Figure 6

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police currently use the above model as both an Incident Management model, and as a Use of Force model. It is a form of a linear, or incremental model, in that it does display the progressive levels of Force. It also shows five basic risk levels of the suspect. The Use of Force responses are not clearly defined for each risk level, and I feel this is a step in the right direction. Australian agencies push for the use of the minimal amount of force used by our Police, and this model displays these options, although they seem a little "vague".

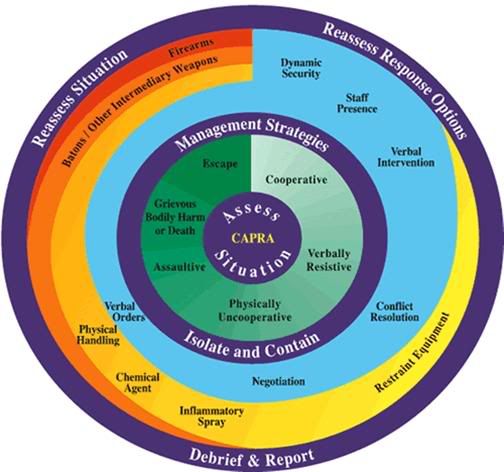

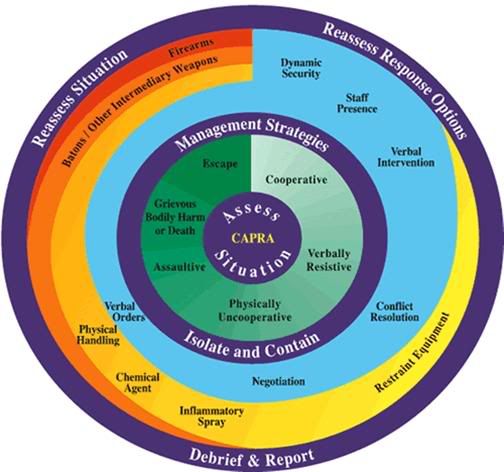

Strangely enough, Canadian Law Enforcement agencies seem to be converts of circular models. Below is the Situation Management Model used by the Correctional Service Canada, (CSC). The "blurb" associated with this model is that "CSC Staff and Management will prevent, respond and resolve situations using the safest and most reasonable intervention."

Figure 7

What does this model show us? Would it assist Police Officers to select the appropriate option to resolve an incident? It does outline appropriate responses to suspect's actions. It is not rigid in each response, hence allowing "minimal" force. It is a fairly clear illustration of options and levels for outside interests, and also meets my third requirement of showing the need to constantly re-evaluate our options. Although geared towards a Correctional Services requirement, this is definitely a good example of what a Use of Force model should be.

But what else is there?

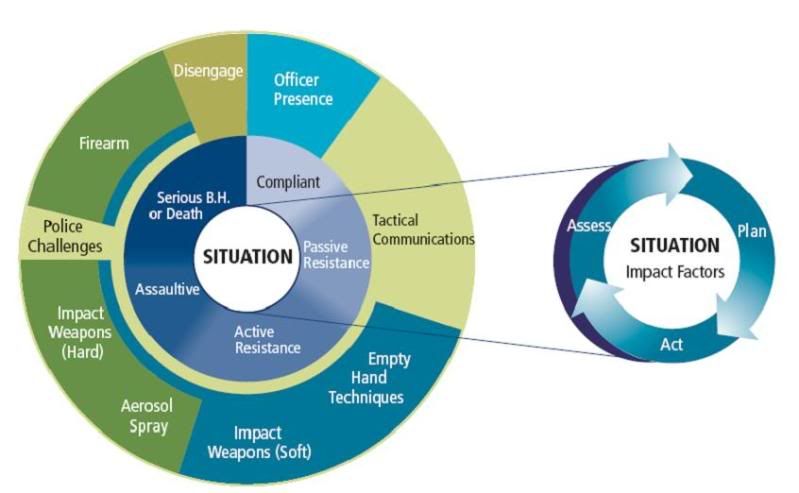

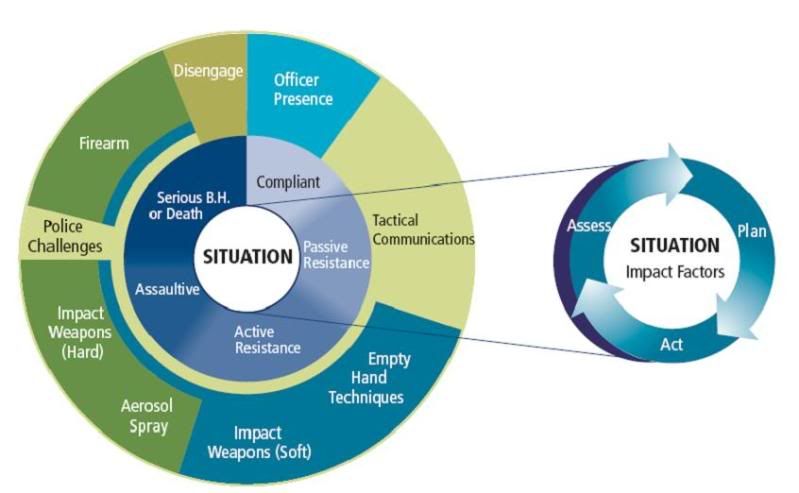

Figure 8

Figure 8, being the Ontario Use of Force model, was created in 1993 by the Ontario Provincial Police, Canada, (hmmm, there's Canada again). This model, although circular like our current Situational Tactical Options Model, also shows the incremental progression of Force options, and how they relate to one another. There is no random / confusing assignment of each option.

Additionally, the Ontario Model is useful in that it relates specific use of force levels to the threat presented to Police. It is a clear representation of what actions by Police can be in response to the actions of the suspect / client, and that communication is a permanent consideration. It further indicates in the second "insert" model that any response must be continually re-evaluated. This model, even though it is 15 years old, is one that fits into all three of my requirements for a Use of Force model. However, the responses of Police appear more "fixed" than that of the CSC model, which although make it a good training tool, is most likely not a good for a "minimum force" policy currently used by Australian agencies.

And that is an additional consideration that must be studied. If a Use of Force model clearly outlines appropriate responses for training by Police, would that model also suit the requirement to clearly illustrate the appropriate options to outside parties? It is a fact of life that policy and training tools will be studied in court, and a model needs to be able to withstand that scrutiny.

But does that mean models should be vague for the Police using them in an effort to reduce the amount of legal liability towards the Police organisation?

Australian Police agencies need to take a certain amount of responsibility for the actions of their Officers. Showing them an ambiguous model, and sending them to deal with violence, and then expecting those same Officers to justify their actions in Court is not sufficient, and that current thinking in use today needs to be abandoned. It is simply a form of neglect.

Providing those same Officers with a clear-cut guide in the form of one similar to the Ontario Use-of-Force model, or the CSC model is an action that not only allows Officers to make the correct decision during times of extreme stress, but allows the community and the media to understand why Police did what they did.

There is another model which I would like to bring your attention to. The Use of Force – Sector Model was created in 2003 by Ken J. Good of Strategos International. Mr Good has a vast wealth of experience and knowledge, and you would do well to research him and his training. But his Use of Force – Sector Model, is worth noting.

Figure 9

This model could be described as an evolution in Use of Force models. It is useful as a training tool, a court and media justification illustration, and as a policy model. We can see the different levels of Use of Force and how they relate to each other. The responses to suspects' actions are defined but not confined to specifics, allowing for the consideration of minimal appropriate responses. For example, it shows that OC spray is not appropriate for an edged weapon attack, but indicates that Taser is the minimal appropriate option. It provides a clear illustration, to both Police and outside interests, or what an appropriate option is for any given scenario. And lastly, but most definitely not least, it shows the requirement to constantly re-evaluate the situation, and appropriate options. "OODA" in the centre of the model, shown as a constantly revolving process, is the process that every Officer needs to undertake in any given incident. It is "Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act." This needs to be undertaken constantly.

But again the arguments will ensue from those people too lazy to change. They will try to argue that North America is not Australia, and we should not use the same policies or models as them. Although it is obvious that this is a weak argument, why don't we take a look at what our New Zealand colleagues use. Remember, NZ Police first responders are not usually armed, and the belief there is that there is not sufficient crime to justify it. One would think that their Use of Force policies / models would then be similar to Australia.

Think again.

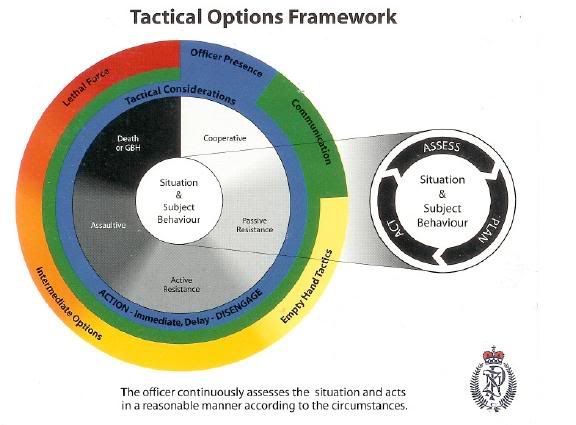

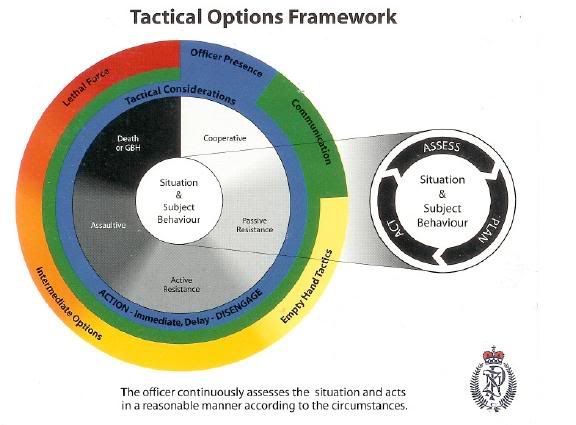

Figure 10

Being very similar to the Ontario Use of Force Model, again we see an incremental model that clearly relates Police use of force responses to the threat perceived. There is a clear outline of what force is appropriate, and what is not. There is the clear requirement for Police to continually assess the situation, to "communicate" as well as providing the option to "disengage" at all times. The colour-codes allow for ease of explanation not only in training, but in Court and to the public via the media.

This Tactical Options model is provided to NZ Police on a laminated card which they can keep in their Uniform or gear bag for easy reference. This is an intelligent move by NZ Police, and shows that the organisation is willing to take responsibility for the amount of force used by its Officers, as opposed to Australian organisations who seem happy to throw a jumble of options at their Officers and then expect them to make the right decision during periods of extreme stress.

Does this model meet the three criteria we were looking for?

1. Assists Officers to select the appropriate option to achieve a safe and effective response to a variety of scenarios;

2. illustrates clearly appropriate options to outside parties; and

3. Clearly show the requirement to constantly re-evaluate available options.

Instead of me trying to sell it to you, I will let you read the criteria and study the model to see if it does. I'll let YOU decide.

My personal recommendation is that Australian Police organisations amend their policies to reflect accepted training principals, and issue their operational staff with a laminated Tactical Options Model similar to that issued to NZ Police Officers. This is to assist Officers in making the safest and most appropriate decision regarding what force should be used in any given situation, instead of expecting them to choose an option at random as is currently the expectation.

As the saying goes, "A picture is worth a thousand words." Our Police need the best "picture" to allow them to do their job.

"Which is a greater use of force? Punching someone, or pepper-spray?" If I had a dollar for every time I heard that question, I'd probably be riding a gold-plated Harley Davidson to my 100-foot yacht by now. The reason that question was asked so frequently was because neither legislation nor policy sufficiently explained the relationship between certain Use of Force options. Have you been trained enough to answer that question to a jury of your "peers"? How about to an internal investigator, or one from CMC / OPI etc?

In 1994, the Victoria Police conducted PROJECT BEACON, which was a training program in response to public (and media) outcry about the number of people shot by Victoria Police. (I am in no way criticising Victoria Police Officers for their Use of Force at that time.)

Part of this project was the establishment of a Tactical Options model that was to be taught to all Victorian Police Officers. This Model was then taught by other jurisdictions, and eventually made its way into the National guidelines in 1998, and again in 2004.

Figure 1

Let me point out some basic ideas behind this Situational Tactical Options Model, (see figure 1), which I have directly quoted from the National guidelines for incident management, conflict resolution, and use of force: 2004:

"Such a model provides a mechanism to aid police officers in the management of incidents";

"the model assists police officers to select the most appropriate option to achieve a safe and effective response to a variety of scenarios";

"Incremental models illustrate a step-by-step, linear progression in the level of force that is appropriate according to the level of resistance/threat displayed by a suspect/detainee, from minimal force (e.g., officer presence, verbal communication) to lethal force (e.g., firearms). There are two fundamental problems with the structure of incremental models. First, they imply the need to move through the incremental progression one step at a time. As a result, such models are very restrictive in terms of the tactical options available for selection at any point in time. Second, they can be viewed as uni-directional. This limits the scope for de-escalation of the incident";

I will comment on each point separately. Firstly, point 1 states, "Such a model provides a mechanism to aid police officers in the management of incidents". This point I agree with, and is one that needs to be understood by all. This model assists officers in the management of an incident.

Too many agencies in Australia are teaching our Police this model as an example of how to decide upon which Use of Force option to use. This is a dangerous practice that needs to cease. This is not a Use of Force model but a Situational Tactical Options Model. It is something that should be used by the senior Police Officer at an incident to refer to when resolving an incident. It is not a learning tool for Use of Force training.

"Hick's Law", to greatly simplify, states that the more options to choose from, the longer it takes to choose an option. If a Police Officer is faced with a threat, especially a potentially lethal threat, then that Officer's training should be such that they know exactly what option to choose in that situation. They should not be thinking about some ambiguous model with a multitude of options displayed in random order, most of which are not relevant to that particular situation.

The Association of Independent Schools, Queensland, (AISQ), created a research brief titled Best Practices in Teaching and Learning: What does the research say? (2001).

This brief outlines that the human brain learns patterns:

The search for meaning occurs through patterning. The brain is both artist and scientist. It is designed to perceive and generate patterns, and it resists having meaningless patterns imposed upon it (Hart, 1983; Lakoff, 1987). Meaningless patterns are isolated pieces of information that are unrelated to what makes sense to a student.

Implications for education: Learners are patterning or perceiving and creating meanings all of the time in one way or another. We cannot stop them, but can influence the direction that their learning takes. Although we select much of what students are to learn, the ideal process is to present the information in a way that allows the brain to extract patterns, rather than try to impose patterns.

So is a random assortment of use of force options better to teach Police with or an incremental model in a clear pattern that also articulates what force options should apply to particular threats? It seems obvious that a clearly-defined model is better to learn and understand than something designed to be ambiguous.

Point 2 - "the model assists police officers to select the most appropriate option to achieve a safe and effective response to a variety of scenarios." Ok, can anyone explain to me exactly how this model is supposed to do this? Police Officers do not carry around a copy of this model in their pockets to refer to when they attend at an incident. Too many, actually all, Australian police agencies think that displaying a model during a lecture will train Police to be able to cope with a critical incident in the future. To be blunt, this is a load of bull droppings.

The ONLY training method that will assist Police in the management of incidents is to firstly teach them the laws, policies, and methods in the classroom, and then rigorously train them and test them in extensive practical exercises. Staring at a model on a Powerpoint presentation, considering that the human brain can not easily memorise multiple components of a non-linear / non-pattern model, is not an effective training tool for managing a complicated incident under stress.

And how can an Officer, much less a member of the public or media, look at this ambiguous model and understand what the appropriate response is to an offender's actions? How would anyone be able to use this model to justify any level of Force used by Police?

Point 3 – "Incremental models illustrate a step-by-step, linear progression in the level of force that is appropriate according to the level of resistance/threat displayed by a suspect/detainee, from minimal force (e.g., officer presence, verbal communication) to lethal force (e.g., firearms). There are two fundamental problems with the structure of incremental models. First, they imply the need to move through the incremental progression one step at a time. As a result, such models are very restrictive in terms of the tactical options available for

selection at any point in time. Second, they can be viewed as uni-directional. This limits the scope for de-escalation of the incident"

I have major issues with this point, especially as it assumes that the model in Figure 1 assists Police in choosing a Use of Force option. Stating that a linear model implies anything is an illogical explanation chosen only to justify the authors' bias. There is no evidence to suggest teaching Police progressively different levels of Force means that they will start at the bottom and work their way up, or down. It is a clear guideline of where each Use of Force sits, and not a "map" to follow step-by-step.

Additionally, a linear Use of Force model (see figure 2) is easier to explain to a Jury (and to the media), and assists in the learning process of Police officers, and their justification of Use of Force. A linear model shows the relationship between each Force option, and clearly illustrates to both Police and outside parties where each stands. There is no confusion as to which is greater.

Figure 2

The above points alone should be sufficient to not use the non-linear model in Use of Force training. The linear, or incremental, model allows crystal clear explanations and understanding of Use of Force by Police. Also, how many times have you read some "expert" in the media claiming that the Use of Force used by Police was excessive, and they should have used another option? Imagine if your Organisation (or your Union) could point to a linear Use of Force model to show that what the "expert" suggests is plainly incorrect?

Lastly, point 3 also states that a linear model "limits the scope" for de-escalation of Force. Say again? I am tired of academics and Police Managers assuming that frontline Police do not have the mental capacity to understand something, in an effort to justify not teaching a tactic. Ask yourself, how difficult is it to understand that if you use a particular level of force against a particular threat, and that threat is reduced, you reduce your level of force in response? Considering that Australian Police organisations are attempting to have Policing recognised as a "Profession", then our Managers and Academics should realise that today's Police Officer is a "professional". In other words, our Police Officers aren't as dumb as these guidelines insinuate.

To put it in "layman's" terms, do you really think that the Police Officers in our nation will not understand the concept of de-escalation of Force? And if you do not think they are intelligent enough to understand that concept, do you think the ambiguous models currently used will assist them?

The work done by Australian Police agencies to ensure that our Police use the minimum amount of force needed to resolve an incident is commendable. Our society expects our Police to resolve an incident with the minimum amount of force necessary, and to not be like "Dirty Harry" in their approach to offenders. However, when it comes to Use of Force, it should be emphasised to the public that Police will use the minimum appropriate force, and not just "the minimum". If the minimum force appropriate to a situation is spending ten hours talking to someone, then so be it. But that does not mean the very next incident does not justify punching a suspect, or even shooting them to defend the life of an innocent. Sometimes lethal force is the minimum appropriate, and though there will always be critics of this, society at large will understand this concept. However, having guidelines and diagrams to show the public and media will greatly assist in the explanation and justification of the "appropriate" amount of force used by Police.

Naturally the argument will arise that current training models and methodologies are suitable. Well, are they?

In February this year, the Executive Leadership Group (ELG) of the NT Police Force sent out an organisation-wide notice, which stated, "A decision has been made to raise the level of force to which Tasers can be applied. The intent of the amendments by ELG is to place the Taser just under that of the firearm and to ensure that all other options are ruled out before the Taser is applied."

Can anyone relate that to the circular and ambiguous Use of Force model that 7 out of 8 Australian Police organisations (including NTPol) use? They are effectively saying that the circular model is not sufficient, and are clearly defining the use of an incremental Use of Force model by ordering their staff to "place the Taser just under that of the firearm".

The problem with NTPol's directive is that is very restrictive in the usage of a particular force option, which seems to be guided more by an intent to protect the organisation than it is to providing useful and effective guidance to the Officers facing threats on the streets.

On the 17th of March this year, the Queensland Coroner reviewed four Police shootings. Although he cleared Police of any wrong-doing in relation to the actual Use of Force, the Coroner stated:

"I recommend that the Queensland Police Service review the operational skills training provided to officers..."

"Despite the earliest of these shootings occurring four years ago, no review of the incidents has been undertaken by the QPS to consider the conduct of its officers or the suitability of its policies and procedures....no opportunity for organisational learning has been utilised."

It should be obvious that reviews of incidents, policies and methodologies should be continually assessed, especially when the phrase "Continuous Improvement" is bandied about so much, but unfortunately it does not happen as frequently or as in-depth as it should. Just because your Use of Force policies and training models have not yet been criticised as lacking by a Coroner, does that mean it is perfect? Of course not.

Fortunately, there are other options out there, some of which are confusing or dated, but actually provide valuable training and policy tools to our Police. The preferred endstate of a Use of Force model, accepted by a Police organisation is one which "assists police officers to select the most appropriate option to achieve a safe and effective response to a variety of scenarios." I also propose that an organisation's Use of Force model should illustrate to investigators, the court, or a jury, what the appropriate level of force is in any given situation. It should also highlight the dynamic and fluid nature of incidents. So, I will examine some options with the following three guidelines:

1. Assists Officers to select the appropriate option to achieve a safe and effective response to a variety of scenarios;

2. Illustrates clearly appropriate options to outside parties; and

3. Clearly show the requirement to constantly re-evaluate available options.

Use of Force models have been around for a while. Let's look at figure 3.

Figure 3

This model was used by the Los Angeles Police department in 1978, and was called a "Force Continuum Barometer". It clearly shows both a linear explanation of the Use of Force options available to Officers, as well as what is an appropriate Force option in relation to the actions of a suspect. This clearly shows a trainee or a jury what is appropriate or not. However, although it would have been a useful tool 30 years ago, it does not truly reflect the fluid nature of Policing. Neither does it reflect the tools at a contemporary Police Officer's disposal.

Figure 4

The "confrontational continuum", created by Dr Kevin Parsons in 1980, is an early attempt at trying to reflect the different aspects of suspects and their behaviour in a model that would assist Police in their responses. Again, this model clearly shows where each Use of Force option sits in a linear progression, which assists in training and justification of Force. Again, although it was probably a ground-breaking model in it's time, it fails to display the third point that I am assessing these options on. There is no indication of continuous evaluation.

Figure 5

The above model, created in 1983 (and described as the "Original" Use of Force model), is again a linear progression chart, describing both the suspect's resistance levels, with corresponding appropriate Use of Force options. Although also showing the levels of Use of Force available to Police, it is a confusing model which also limits options of Police to the green area. This would be useful in limiting the number of options available to Police, (keeping in mind "Hicks Law"), but in this day and age of legal liabilities and the policy of minimum force, I can see this model as being a lawsuit waiting to happen.

As you can see, these models have not been getting simpler, nor do they show the Use of Force options in a random pattern, but clearly articulate where each Use of Force option sits in relation to other options. Remember, this is important in training Police in appropriate Force levels; assists Police in justifying their actions; and provides a clear representation of levels of force and appropriate options to those persons with outside interests.

Figure 6

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police currently use the above model as both an Incident Management model, and as a Use of Force model. It is a form of a linear, or incremental model, in that it does display the progressive levels of Force. It also shows five basic risk levels of the suspect. The Use of Force responses are not clearly defined for each risk level, and I feel this is a step in the right direction. Australian agencies push for the use of the minimal amount of force used by our Police, and this model displays these options, although they seem a little "vague".

Strangely enough, Canadian Law Enforcement agencies seem to be converts of circular models. Below is the Situation Management Model used by the Correctional Service Canada, (CSC). The "blurb" associated with this model is that "CSC Staff and Management will prevent, respond and resolve situations using the safest and most reasonable intervention."

Figure 7

What does this model show us? Would it assist Police Officers to select the appropriate option to resolve an incident? It does outline appropriate responses to suspect's actions. It is not rigid in each response, hence allowing "minimal" force. It is a fairly clear illustration of options and levels for outside interests, and also meets my third requirement of showing the need to constantly re-evaluate our options. Although geared towards a Correctional Services requirement, this is definitely a good example of what a Use of Force model should be.

But what else is there?

Figure 8

Figure 8, being the Ontario Use of Force model, was created in 1993 by the Ontario Provincial Police, Canada, (hmmm, there's Canada again). This model, although circular like our current Situational Tactical Options Model, also shows the incremental progression of Force options, and how they relate to one another. There is no random / confusing assignment of each option.

Additionally, the Ontario Model is useful in that it relates specific use of force levels to the threat presented to Police. It is a clear representation of what actions by Police can be in response to the actions of the suspect / client, and that communication is a permanent consideration. It further indicates in the second "insert" model that any response must be continually re-evaluated. This model, even though it is 15 years old, is one that fits into all three of my requirements for a Use of Force model. However, the responses of Police appear more "fixed" than that of the CSC model, which although make it a good training tool, is most likely not a good for a "minimum force" policy currently used by Australian agencies.

And that is an additional consideration that must be studied. If a Use of Force model clearly outlines appropriate responses for training by Police, would that model also suit the requirement to clearly illustrate the appropriate options to outside parties? It is a fact of life that policy and training tools will be studied in court, and a model needs to be able to withstand that scrutiny.

But does that mean models should be vague for the Police using them in an effort to reduce the amount of legal liability towards the Police organisation?

Australian Police agencies need to take a certain amount of responsibility for the actions of their Officers. Showing them an ambiguous model, and sending them to deal with violence, and then expecting those same Officers to justify their actions in Court is not sufficient, and that current thinking in use today needs to be abandoned. It is simply a form of neglect.

Providing those same Officers with a clear-cut guide in the form of one similar to the Ontario Use-of-Force model, or the CSC model is an action that not only allows Officers to make the correct decision during times of extreme stress, but allows the community and the media to understand why Police did what they did.

There is another model which I would like to bring your attention to. The Use of Force – Sector Model was created in 2003 by Ken J. Good of Strategos International. Mr Good has a vast wealth of experience and knowledge, and you would do well to research him and his training. But his Use of Force – Sector Model, is worth noting.

Figure 9

This model could be described as an evolution in Use of Force models. It is useful as a training tool, a court and media justification illustration, and as a policy model. We can see the different levels of Use of Force and how they relate to each other. The responses to suspects' actions are defined but not confined to specifics, allowing for the consideration of minimal appropriate responses. For example, it shows that OC spray is not appropriate for an edged weapon attack, but indicates that Taser is the minimal appropriate option. It provides a clear illustration, to both Police and outside interests, or what an appropriate option is for any given scenario. And lastly, but most definitely not least, it shows the requirement to constantly re-evaluate the situation, and appropriate options. "OODA" in the centre of the model, shown as a constantly revolving process, is the process that every Officer needs to undertake in any given incident. It is "Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act." This needs to be undertaken constantly.

But again the arguments will ensue from those people too lazy to change. They will try to argue that North America is not Australia, and we should not use the same policies or models as them. Although it is obvious that this is a weak argument, why don't we take a look at what our New Zealand colleagues use. Remember, NZ Police first responders are not usually armed, and the belief there is that there is not sufficient crime to justify it. One would think that their Use of Force policies / models would then be similar to Australia.

Think again.

Figure 10

Being very similar to the Ontario Use of Force Model, again we see an incremental model that clearly relates Police use of force responses to the threat perceived. There is a clear outline of what force is appropriate, and what is not. There is the clear requirement for Police to continually assess the situation, to "communicate" as well as providing the option to "disengage" at all times. The colour-codes allow for ease of explanation not only in training, but in Court and to the public via the media.

This Tactical Options model is provided to NZ Police on a laminated card which they can keep in their Uniform or gear bag for easy reference. This is an intelligent move by NZ Police, and shows that the organisation is willing to take responsibility for the amount of force used by its Officers, as opposed to Australian organisations who seem happy to throw a jumble of options at their Officers and then expect them to make the right decision during periods of extreme stress.

Does this model meet the three criteria we were looking for?

1. Assists Officers to select the appropriate option to achieve a safe and effective response to a variety of scenarios;

2. illustrates clearly appropriate options to outside parties; and

3. Clearly show the requirement to constantly re-evaluate available options.

Instead of me trying to sell it to you, I will let you read the criteria and study the model to see if it does. I'll let YOU decide.

My personal recommendation is that Australian Police organisations amend their policies to reflect accepted training principals, and issue their operational staff with a laminated Tactical Options Model similar to that issued to NZ Police Officers. This is to assist Officers in making the safest and most appropriate decision regarding what force should be used in any given situation, instead of expecting them to choose an option at random as is currently the expectation.

As the saying goes, "A picture is worth a thousand words." Our Police need the best "picture" to allow them to do their job.